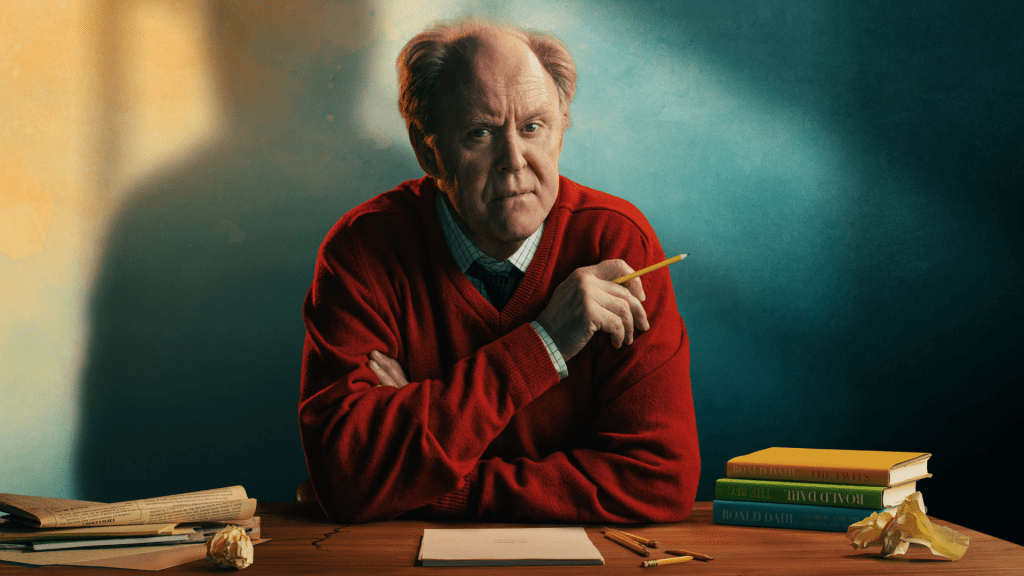

As writer Mark Rosenblatt’s first ever play, this is a hell of a debut. Winner of three Olivier awards, including “Best Play”, “Giant” is set across a single afternoon in 1983 and focuses on children’s author Roald Dahl as he deals with the media fallout of a particularly contentious book review that he has written. As Dahl, John Lithgow delivers a powerhouse of a performance, at one moment appearing as the kindly, grandfatherly figure we would expect of one of the most celebrated children’s authors, and the next minute becoming something much more monstrous and unforgivable, as his questionable views on Israel and his blatant antisemitism are thrust into the limelight.

The play begins as one might expect a fictional account of Dahl to begin. Various bestsellers are name-dropped, as is Dahl’s collaborator Quentin Blake, when Dahl meets with his British publisher Tom Maschler (Elliot Levey, fresh from his role as Polonius in the RSC’s Hamlet) to discuss the upcoming publication of his new book The Witches. Lithgow’s Dahl comes across initially as a little short-tempered, his anger flaring up occasionally at the noise coming from the builders renovating his house, but overall he appears generous and likable, quick to come out with a humorous remark, and sharing excellent rapport with Levey’s Maschler. We are also introduced to Dahl’s fiancé Felicity (Rachael Stirling), and a little of Dahl’s backstory is subtly explored – he is newly divorced from his first wife of 30 years, following an affair that had continued with Felicity for the last 11. There is more to this kindly, elderly gentleman than meets the eye.

It is the arrival of Aya Cash’s Jessica Stone, Dahl’s US publisher, that throws a spanner in the works, as she openly begins to confront Dahl about the recent book review. The review is alluded to throughout the first act – we learn that, as a result, people have been making threats towards Dahl and his family, and a policeman has been stationed at the door. This culminates in Cash delivering a verbatim reading of the review at the end of the opening act, which contains language and phrases more shocking than the audience could imagine. Could this really come from the children’s author we all thought we knew so well?

The second act doesn’t hold back, as we get a true glimpse into the vicious thoughts inside Dahl’s head, taking his anger out on Stone and Maschler, who are both Jewish themselves. Stone is more willing to challenge Dahl to begin with, hoping to rattle him enough that he admits his views are wrong, stating that he cannot tarnish all Jews with the same brush despite the unforgivable acts by the Israeli army in West Beirut during the Lebanon War. Dahl does not back down, however – his reaction and dismissive nature speaks to his sexist views as well as his anti-Zionist views. He stereotypes all Jews, referring to them as greedy and materialistic, cursing them for “controlling the media”.

Maschler tries to reason with Dahl, even supports him against Stone for a while, until the ferocity of Dahl’s views becomes too much for him to bear. Dahl ridicules Maschler’s escape from the hands of the Nazis as a child, and questions the role of Maschler’s father during the war. Throughout, Felicity is caught in the crossfire. The action on stage is mesmerising – one hardly draws breath as this battle of wills, politics and philosophy plays out amongst the Dahls’ partially renovated dining room.

And yet Dahl isn’t in any way portrayed as a one-note villain. He swings on an axis between good and evil; one moment he is chastising Stone for her religious views, the next he is signing a copy of The Twits for her disabled son, and speaking openly about his experiences with his own disabled child. Aspects of Dahl’s life, including the death of his daughter at the age of 7, are touched on, creating a much more complicated figure that is impossible to simply hate. Dahl is given so many opportunities to apologise, to take back what he said, but instead he chooses to double down, unwilling to make any kind of concession. He is headstrong, bullish and foolish. It makes for a frustrating, yet compelling, watch.

As Dahl’s maid Hallie, Tessa Bonham Jones offers yet another aspect of such an important debate, as the role of someone who quietly observes, yet keeps her mouth shut and offers no views. Dahl makes multiple attempts to draw her in, asking her opinion, and even shouting at her for hearing the debate and yet saying or doing nothing. It makes the audience question their own position, especially in light of the tragic events of October 7 2023, and the ongoing situation in Israel and Palestine. People will emerge from this play with different views, but the fact that they have those views, that this play has allowed them to form those opinions, is what is important and makes this play so vital.

Bob Crowley’s set is simple yet detailed – a dining room in a state of disrepair, wires poking out of walls, windows masked by plastic sheeting, boxes of possessions piled in the back corner. Under Nicholas Hytner’s direction, each character soars, feeling fully fleshed out. Even Richard Hope’s groundskeeper, glimpsed only for a few minutes, is fully realised as a similar male companion to Dahl, who draws out his lighter side as Dahl discusses the possibility of a knighthood (a possibility that is to never come to fruition).

The play may feel a little circular and drawn out in places, with themes constantly revisited without either side making any ground, but that is the nature of such a complicated conversation where feelings are running so incredibly high. This play is timely, important and wholly absorbing. Two and a half hours pass by in the blink of an eye. This is the story of a completely fictional, yet utterly possible, meeting between Dahl and his publishers, and yet in the final moments of the play, as Dahl telephones The Times in order to make his position clear, those are Dahl’s own words, cleverly drawn from multiple different sources and reorganised into a single speech. It is absolutely true to Dahl’s own opinions, and it is utterly horrifying.

Tom Morley, July 2025

For more information on how I decide on star ratings, see here: Star ratings – Broken Legs Blog

Review round-up:

The Guardian: Giant – A four star review from The Guardian, who commend the “sophisticated writing” but point out that the “ground is inherently lopsided – the opposing arguments around Israeli and Palestinian freedom cannot be weighted equally when one is fuelled not only by a sense of righteous injustice but also bigotry.”

Time Out: Giant, Harold Pinter Theatre – A 5 star review from Time Out, who point out that the “nastiness is real” whilst, thanks to Hytner’s direction, “humour is never many lines away”

All That Dazzles: Review, Giant, Harold Pinter Theatre – ATD also award the show 5 stars, who conclude by saying “Giant is complicated but so is life, and this play is one that will have you leave the theatre, debating what you have just seen and the real-life repercussions of it“