Based on the novel by Yann Martel, and adapted for the stage by Lolita Chakrabarti (who previously adapted RSC’s Hamnet), “Life of Pi” explores big ideas around religion and belief, with the story told through the eyes of 17 year old Pi Patel (Divesh Subaskaran). This is Subaskaran’s professional acting debut – thrown in at the deep end with a role that never lets up throughout the play’s 2 and a half hour run time, although this doesn’t phase him. Subaskaran is such a natural on the stage it’s as though he was born for this role. The role is even more of an ask when you consider that his main co-star throughout the play is a Bengal tiger… but more on that later.

The play begins in India in 1976, where Pi and his family own a zoo. Various animals from the zoo are brought to life by impressive puppets, including zebras, hyenas and a mother and baby orangutan. Even a giraffe’s head is seen briefly, poking its head round the corner of the stage! Pi’s father (Ralph Birtwell) tries to teach his son about the dangers posed by the animals, and we get the sense that the play hides darker themes beyond the puppet spectacle when the family’s pet goat is killed. This is a shocking moment that occurs at the beginning of the play, and really makes the audience sit up and pay attention. This is not The Lion King.

The family are welcoming a new member in the shape of Bengal Tiger Richard Parker. This puppet is the true main star of the show, and the design (by Nick Barnes and Finn Caldwell) is very impressive. The tiger is incredibly realistic, piloted by 5 cast members at a time, including Sebastian Goffin, Akash Heer, Romina Hytten, Kate Kennedy-Rose, Aizah Khan, Kate Rowsell and Tom Stacy – the puppeteers interchanging between the tiger and the other puppets as necessary. It is clear that this is a dangerous beast, each movement from the puppeteers careful and calculated and constant.

Following the death of his goat, Pi begins to explore religion, and this is at first treated in a slightly comical way – he casually strolls from the mosque to the temple to the church, finding benefits to all of them and not understanding why he needs to choose. The themes are treated in more serious ways in the second act, and the distinction between fact and fiction, story and truth, good and bad is explored through the tale that Pi tells, and then re-tells in a different way.

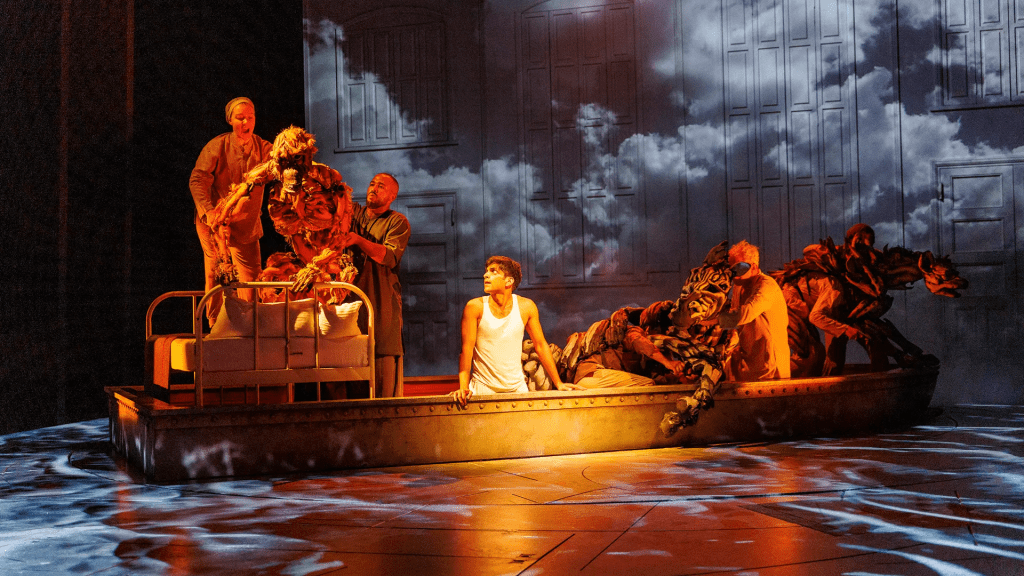

The family is forced to emigrate to Canada following the declaration of “The Emergency” by the Indian Prime Minister. They get passage on board a large container ship, taking the zoo animals with them. Whilst at sea, the ship begins to sink, and the special effects which bring this to life are mind-blowing. Water is projected onto the floor, as the cast and the puppets throw themselves about the stage in time to the rocking of the ship. As Pi falls into the water, he is lifted aloft by the other cast members to give the sense of him swimming. A sea turtle swims past him. Then a zebra.

Pi finds himself on board a lifeboat. His company – a zebra, a hyena, an orangutan and Richard Parker, the ferocious Bengal Tiger that makes the auditorium shake as he roars. From there, the second act focuses on character rather than spectacle, and it is this more quiet, introspective act where the play truly soars. Pi is helped along on his journey by visions of his mother (Goldy Natay) and sister (Sonya Venugopal) but they are almost superfluous – the entire stage belongs to Subaskaran, and his skill combined with the clever storytelling techniques of Martel/Chakrabarti make for a riveting second act where it is impossible to tear your eyes from the stage.

A magnificent, awe-inspiring piece of theatre. The special effects and the puppetry is no doubt impressive. But it is in the story where the play truly stands out.

Tom Morley, April 2024